In the Driverless City, How Will Our Streets Be Used?

A glut of speculative plans reimagine the future streetscape. But is it a road to nowhere?

Courtesy Carlo Ratti Associati

Many of our hopes and anxieties surrounding the advent of the so-called smart city find their clearest expression in the driverless car. Suggesting the prospect of more carefree and efficient transportation as well as the looming cloud of ungovernable technology, autonomous vehicles (AVs) can inspire both fear and optimism (see the outraged response to the 2018 death of a pedestrian struck by a self-driving Uber). And though corporate giants like Tesla, Google, and GM are fast developing marketable prototypes for the vehicles themselves, “alternate land uses will need to be found for these newly ‘feral’ lands that have been freed from parking,” notes Kinder Baumgardner, managing principal of landscape firm SWA, who has done considerable research on the topic.

Urban design and architecture firms like SWA are racing to conceive new (and mostly unsolicited, it should be said) schemes that imagine a near future oblivious to the needs of the private car. The speculative plans all converge on a few key themes, namely walkability, diversity of modes of transport, and a multiplication of public space. “These grand visions will absolutely be realized,” adds Baumgardner. “However, they will be relegated to a few city blocks in a handful of cities as they come face-to-face with the realities of budgets, equity concerns, and human nature.”

The changes associated with driverless cars also touch on issues of privacy. As with other features of the smart city, AVs rely on the massive collection and trafficking of personal data; given that passengers will be stationary during a trip and their destinations and daily routes easily discernible, the technology is perfectly suited to gathering biometric and location data. “The AV will simply further personalize surveillance,” says architect/writer Michael Sorkin, whose think tank Terreform is developing the critical project Stupid Cities. “Although bruited as efficient modernity itself, the smart city represents its horrifying dark side.”

With data and experiences constituting the other, what Baumgardner calls a “mobility experience” may come to pass: technologies intuiting what we want, reducing the number of decisions we’re expected to make, sorting people into like-minded groups and places, and diminishing urban spontaneity to the point of lived homogeneity. Perhaps our rosy imaginings of the future city ought to be recalibrated, or the planning priorities of this century may be as inappropriate as those of the last.

Here we present several speculative plans for the driverless city that engage a range of its precepts. While some are rather fanciful, portending a wholesale Europeanization of urban centers or assuming a technocratic capacity to rework the public realm, others demonstrate a more measured response to specific contexts and challenges.

Roads at Work

Courtesy Carlo Ratti Associati

By nearly all accounts, AVs will have drastically altered the transportation and mobility landscape of cities by the middle of this century. Anticipating those upheavals, Italian-born architect and educator Carlo Ratti proposes two visions for the Boulevard Périphérique, Paris’s ring road that effectively defines the city’s boundaries. In the proposal, obviated car lanes are converted to playgrounds or furnish the space for new residential buildings. Elsewhere, suburban highways in the Île-de-France region are repurposed to accommodate new functions related to the production of energy and more efficient commuting. The central lanes of the A6 highway, for example, can host greenhouses or photovoltaic panels to generate solar energy, while real-time transportation data can streamline commuting and free up space for public use. Speaking at the NEXT Design Perspectives event in Milan last fall, Ratti discussed some of these concepts in relation to Manhattan, which he suggested could operate with just half the number of cars currently on the road.

User Interface

Courtesy Lorinc Vass

The vast overhaul of streetscapes will need to be accompanied by software that enables people to interface with new AV technology. University of British Columbia professor AnnaLisa Meyboom explores this facet in her work on the topic, including her 2018 book Driverless Urban Futures: A Speculative Atlas for Autonomous Vehicles (Routledge). Moribund traffic lights would be repurposed as compass poles that form the basis of any ride-hailing service. Mobility apps would bring together all modes of transportation, both extant and emerging, like electric bikes and kickboards. “Rather than seeing ‘what happens to us’ when the technology arrives, I think we want to design the future,” Meyboom says. “We should be purposeful in how we direct the technology to create the outcome we want to see.”

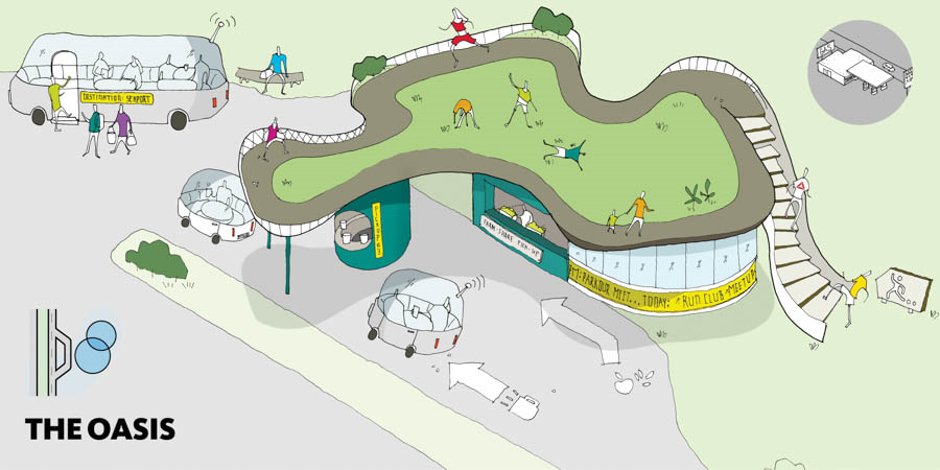

Community Reuse

Courtesy Gensler

As part of a collaboration with Reebok called Get Pumped, global design firm Gensler has envisaged a large-scale adaptive reuse of the nation’s gas stations, which would be rendered superfluous by electricity-powered AVs. “Rather than starting from scratch, designs include and advocate for adaptive reuse whenever possible,” remarks Gensler co-CEO Diane Hoskins, pointing to new uses such as pocket parks, extended bike lanes, and car pickup/drop-off locations. Get Pumped envisions prototypical spaces such as The Oasis, which offers fresh food, yoga and meditation pods, and a running track, and the Community Corner, which transforms a traffic intersection into a social hub.

Company Plan

Courtesy Snøhetta and Plomp

Snøhetta’s smart-city master plan for Ford’s Research & Engineering Center in Dearborn, Michigan, aims to unite disparate buildings, employees, and neighboring communities within a singular Ford “ecosystem.” The proposal calls for the densification of buildings and workers in a central campus hub strung together by pedestrianized “living streets” and an array of shared transportation options. Among these, circulating AVs shuttle employees between meetings and on-campus retreats along a main loop, replacing the large amount of space currently occupied by private-car parking. Though the firm says advances in smart mobility technologies will continually alter the plan, and that “parking needs will be consistently evaluated over the course of project implementation,” it doesn’t do away with personal vehicles entirely: They are simply relegated to the perimeter of the campus.

Mall Rats

Courtesy Natalia Beard

In some American cities, as much as a quarter of downtown space is dedicated to surface parking or garages. Even as driverless futures would stoke dense urban developments, there’s no guarantee they would be enough to support wholesale residential conversions of typologies as profuse as garages. Hospitality and retail spaces will have to fill the architectural gap. Out of SWA, architect Kinder Baumgardner predicts “more creative reuse of parking infrastructure” and even ventures the formation of a parking-garage urban-chic aesthetic that could be marketed by developers. That prognosis may sound like a bit of a stretch, but Baumgardner is unfazed, registering confidence that AVs’ spread into urban life and culture will only continue to grow. (He calls detractors naysayers, nostalgia cases, and “self-driving Luddites.”)

Top Priorities

Courtesy HOK

Diving into the minutiae of street surface changes, American architecture firm HOK has developed several modules for alternatives in the driverless city. A typical two-lane street allocates 60 percent of its width for private vehicles (roughly half for driving, half for parking), with just 40 percent for all other uses. “That disparity extends with wider and busier thoroughfares,” the firm states in a research brief. With parking space slashed and driving space greatly diminished, the question becomes, how should our streets be used? Modules could accommodate a variety of functions, ranging from commerce and culture—which would return the street to its marketplace origins—to recreation. Touching on the latter, one vignette envisions a “forest bath” in the middle of the city, prompting encounters with nature and wildlife ordinarily reserved for rural or peri-rural contexts.

Akiva Blander

Source: Metropolis