Why Are More Cities and Towns Taking on Place Branding?

As more areas invest in new identities, we speak to designers and councils about why this is a growing trend, the benefits a visual brand can bring to a locality and the ethical issues to consider.

From small communities to entire boroughs, new place brands are cropping up at an increasing rate.

Thought to boost tourism, attract investment and boost morale among local people, design studios are being called in to create visual identities for various destinations, in the hopes that a strong brand will bring a range of benefits.

But how effective is place branding and why are so many local authorities and areas investing in it?

While a strong brand is thought to help entice visitors which in turn lifts the local economy, some people such as Ryan Tym, founder and director at studio Lantern, believe tourists are also increasingly looking on a smaller scale when they choose where to travel, leading to smaller areas developing their own identities.

So instead of France, perhaps they are interested in Bordeaux, or rather than London as a whole, maybe its Covent Garden that attracts them. This is where branding a locality comes into play.

Tym, whose studio recently branded London’s Leicester Square, says: “Destinations are always competing for visitors and footfall, so they need to stand out.”

“I think people are becoming more interested in specific areas or parts of cities nowadays. In larger cities, there is more of a requirement for areas to have unique identities.”

He believes this is enhanced by low cost airlines flying to more destinations, forcing cities to work harder to attract visitors.

Civic pride

Empowering residents and boosting morale in a community is another reason for branding a place, such as with Lantern’s project for the Newington Estate on the edge of Ramsgate, a seaside town in Kent.

Home to around 5,000 people, the neighbourhood was chosen to receive £1 million from the lottery’s Big Local fund, putting residents in control of how the money was spent without council involvement.

Previously considered “forgotten” and “underfunded”, Tym says, the community invested in initiatives including credit unions and community gardens and also decided to bring design studio Lantern on board at a discounted rate.

The aim was to create a sense of pride in the area, partly by flipping the concept of an estate from “negative” to “positive”, raising awareness of new initiatives going on in the area and involving more people in decisions around money.

The project included creating branding which has been rolled out on a new website, marketing materials, and a poster campaign encouraging more people to get involved with community matters. It also included a newspaper written by local people and designed by Lantern.

“The concept behind the brand was embracing that there is no shying away from this being an estate but positioning it as an ‘estate of enablers’ and harnessing that positive underdog spirit the community has,” he says.

Branding a council

Others are rebranding for practical reasons, such as local governments restructuring to save money. Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole councils have merged into one new local authority this month, coming under the banner of BCP Council, which will collectively deliver services to residents. A new brand identity has been created as part of the initiative.

Head of communications and marketing at BCP council, Georgia Turner, who has been involved with the rebrand from the start, says defining the aim and audience is important when creating a place identity.

“You need to ask why you are doing it, who for, and what you are trying to achieve,” she says.

In the case of BCP council, the branding is not aimed at tourists, Turner says, but to help residents understand who is responsible for delivering services.

“It’s not about telling people who live here that beaches are lovely,” she says. “They already know that.”

It is also partly about “making the area attractive for investment”, such as from central Government and businesses, she adds, which “tends to go to areas that are succeeding”.

BCP’s process involved designing four different logo concepts, one of which was map-based, one was letters-based and two that were abstract. Two had been designed by in-house council staff and two by outside design studios. The public were then invited to have their say through online surveys, but opinions were “split”.

“Different groups of people liked different things,” Turner says. “Councillors liked a different concept to staff, who liked a different one to residents. Other than taking the map shape, we had to start from scratch.”

As the research was primarily quantitative rather than qualitative, due to time constraints, Turner says they knew what people thought but not “why they thought it”. The organisation was faced with capturing the essence of three existing places, while staying relevant to them all.

To try to solve this, the council team looked for common features of the four concepts, which included creating something “striking” with a “sense of place” and “longevity”, along with a recognition of there being three towns.

The resulting logo features the shape of the area’s coast made up of dots, aiming to create a “digital feel” which Turner says represents the area’s creative sector, with three larger dots reflecting the three towns.

“It has 113 dots representing 76 councillors, 33 wards, three towns and one council,” Turner adds.

Reactions to the logo were mixed, with residents finding the name their biggest problem, Turner says. ’Bournemouth, Christchurch, Poole is a real mouthful,” she says. “A decision was made early on that we would be BCP and there was a bit of local backlash as to how you bring a sense of life or place to three letters.”

People are at the core

In terms of how to brand a place effectively, many agree it is important to involve the people it represents from the start, such as the community and various stakeholders.

For Tym, working on the Newington Estate project began with speaking to residents about their neighbourhood and why they “felt forgotten as an area”, and about positives of where they live, which includes a “very strong sense of community”.

The studio then presented two potential design routes to residents, settling on black illustrations on a coloured background, chosen to be “easier to print and roll out,” he says.

Tym says the outcome has been positive. “It has created a far greater sense of pride in the area, the newspaper has continued and there has been an increase in people attending events,” he adds.

Similarly, when branding Leicester Square, Lantern aimed to speak to a wide range of stakeholders including associations representing local businesses and residents, Tym says. The project was paid for by the Heart of London Business Alliance, a business improvement district (BID) representing companies in Leicester Square and Piccadilly.

The aim was to challenge perceptions, as “there had been a lot of investment in the area, but despite this, its image hadn’t really changed among Londoners,” he says. Some people viewed the area as “a bit of a tourist trap” or only recognised it as a place for film-watching, he adds.

Speaking to local stakeholders helped the studio to create a brand which aimed to tell “some of the lesser known stories” of the area and capture the square’s spirit.

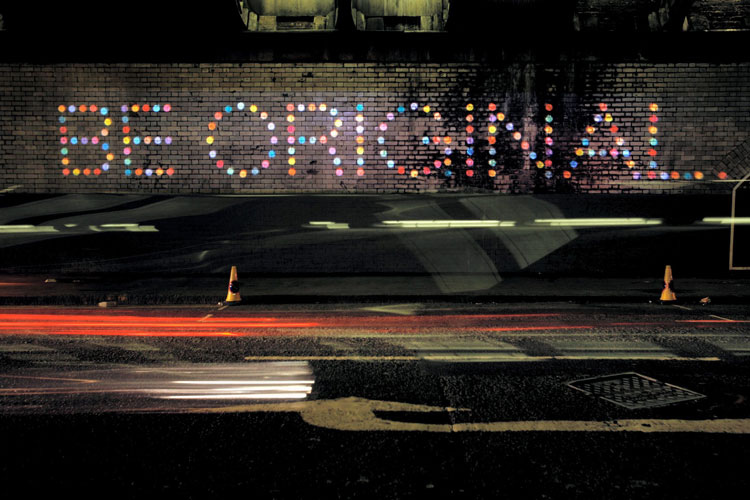

The brand is centred around a logo resembling the letter “L” at an angle, that looks like it is made out of neon lights forming three connected boxes, with the letters “LSQ” inside them.

Marketing materials including posters with brightly-coloured gradient backgrounds, setting out a schedule of things to do in one day in the square, such as “11.47 Lego, 13.04 Lobster, 15.09 Chocolate, 20.03 Cabaret”.

“Embed yourself”

Steve Connor, CEO at Creative Concern has worked on place branding for areas including Manchester, North of Tyne and Aberdeenshire.

The studio worked alongside celebrated designer Peter Saville when he was creative director for Manchester City Council on a long-term project between 2007 and 2013. The work included creating two books for the city filled with “fascinating facts” and data about the area, a new image bank for Manchester and a range of installations.

“If you do not embed yourself and your project [in the community] you will fail,” Connor says.

“We carried out a series of high-level workshops with business leaders, sports leaders, people from the University of Manchester and others,” Connor says.

A similar process applied to several of the studio’s other projects including branding and positioning for Aberdeen, carried out in partnership with Aberdeenshire tourist board, Aberdeen city council and two local universities; Robert Gordon University and the University of Aberdeen, among others. The project has been collectively paid for by all the partners.

The studio created a range of new branding elements including the tagline “Abzolutely” inspired by the city’s airport code ABZ, a new image bank and a new “narrative” for the region, which all stemmed from spending “a lot of time talking to people”, Connor says.

“We wanted to capture the bright future for Aberdeen and put across that it is not just about oil and gas,” he says. “It is a vibrant place with thriving life sciences, great food and drink and lots of castles.”

“It doesn’t happen overnight”

In terms of challenges around successful place branding, Tym and Connor, among others, agree that changing an image of a place takes time.

The entire process in Aberdeen has taken around three years. “We know the image of places is shaped across generations and you cannot change that overnight,” Connor says. “It is something you have to work on for months or years.”

Similarly, Lantern founder Tym believes one of the greatest challenges with place branding is managing expectations of different stakeholders and of those expecting “immediate results”.

Another shared view is place identities need to be more than just a logo or a strapline, but also include assets such as imagery, case studies, key facts, narratives and marketing campaigns — and most importantly, it all needs to be “genuine”.

“You need to make sure there is a strong story running though the brand you are developing, and that it is true to what the area is,” Tym says. “Cultural and historical significance is important, so it is not just starting from scratch but building it up from something.”

When carried out effectively, Connor believes place branding can have a wide range of benefits.

“It can lead to talent attraction; it helps people celebrate reasons that they are proud of an area; it attracts students to study; it helps unlock investment; it encourages people to stay somewhere and build a future; and of course, it helps tourism and the local economy,” he says.

Tym adds: “If you are looking to set up a business or move to a new area, part of the decision-making process involves thinking about whether the values of a place fit with your values as an individual.”

The cost of branding

Despite the benefits, few place branding projects pass without any backlash and there is often criticism around spending public money on design and marketing.

Connor defends the right of authorities to do so but adds that criticism can be expected if it is done badly, such as by not involving local people.

“Cities are vital economic engines… the idea of not spending money on managing the reputation of these places is insane,” he says.

Tym adds it is understandable that people have concerns about authorities spending money on branding but believes “short-term cost” often leads to “long-term saving”. He says branding can add value, but the spend needs to be balanced with the cost of other issues an authority is facing.

Turner, who says the cost of designing the final BCP logo was around £8,000, adds that is it understandable that people question public money being spent on branding at a time when “budgets are being slashed”, but says authorities have a responsibility to create a brand so residents know who is accountable for local services.

She adds that, in BCP’s case, it is only being rolled out across touchpoints where there is a legal requirement to start with, such as on staff badges and parking tickets, and will roll out more widely over time.

Should a local studio work on the project?

While local people are often involved in the decision-making process of creating new place brands, local studios are not necessarily always employed to complete the work. The North of Tyne Combined Authority hired Manchester studio Creative Concern to create its branding, which worked alongside other more regionally-based creatives.

The project involved creating an identity for the area and a series of straplines such as “home of ambition”.

Connor says studios with a “strong track record” of branding places should be able to work outside their immediate footprint but emphasises the importance of working alongside people based in the area.

“We worked with local freelancers and photographers and it was very much done in partnership with locals,” he says.

But while branding a place can make it appear more attractive, some worry this in turn can lead to gentrification, with existing communities being priced out.

Tym says that while this may be a risk, he does not think it is down to branding, but the whole planning of an area, which he says needs to include a mix of affordable housing along with shops and restaurants at different price points to ensure a variety of people feel welcome.

It seems clear that when it comes to place branding, it is hard to please everyone.

Understandably, people tend to have strong connections with where they live or work and branding an area without getting the community on board shows poor judgement, especially if public money is involved.

Stories behind a place are important, and capturing these by talking to the people who know and live them seems like a responsible way to encourage those people to support a project. When it is done right, place branding can be a powerful thing, boosting civic pride, attracting tourism and investment, and empowering communities.